Frank Moorhouse, the celebrated Australian author, and essayist best known for the Edith trilogy, died at 83.

His publisher, Penguin Random House, confirmed on Sunday that he had died at a hospital in Sydney that morning.

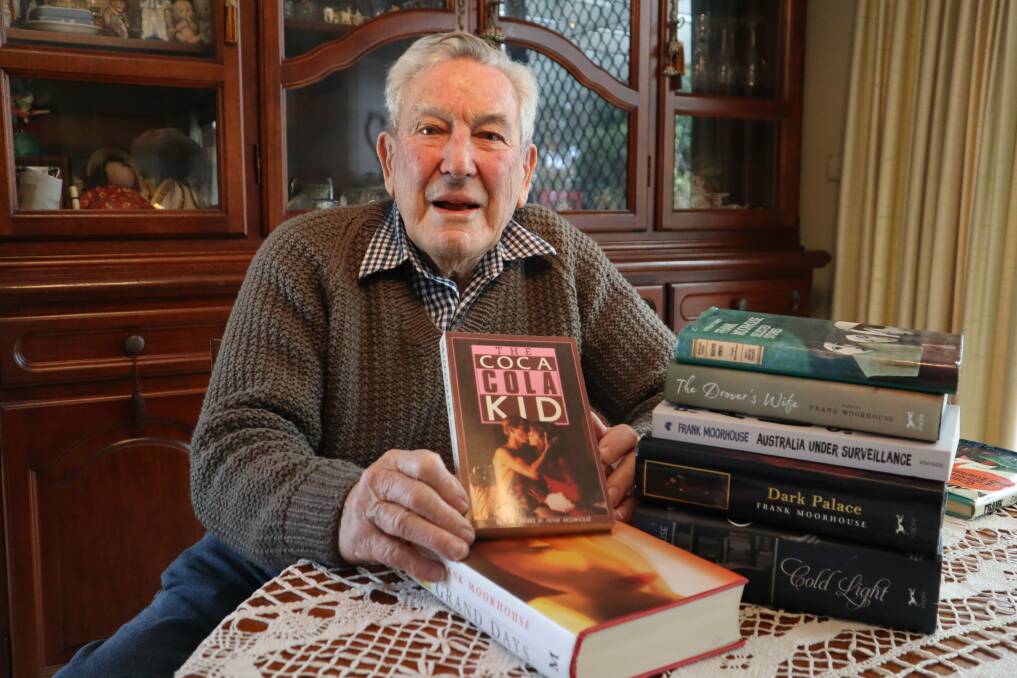

The author of 18 books, in addition to screenplays and essays, Moorhouse explored the Australian identity through the career of Edith Campbell Berry, a young woman who works as a diplomat in Europe, then Canberra, in three novels published between 1993 and 2011.

Grand Days, set in 1920s Europe, was judged to be ineligible for the Miles Franklin literary award in 1994 because it was deemed insufficiently Australian by the judges. This decision led to Moorhouse taking legal action. Dark Palace, the second book in the trilogy, won the prize in 2001, while Cold Light was shortlisted for it in 2012.

The ABC journalist Annabel Crabb, a great fan of Edith Campbell Berry, said: “I know she resonates with a lot of ambitious, energetic, imaginative, and slightly shambolic women – I have always identified very closely with her. What was remarkable about Moorhouse was how he could write her in such a wise way. His gender fluidity marked him. He was a genuine artist.”

Moorhouse was the youngest of three brothers born in Nowra, New South Wales, in 1938. He settled on his future career at 12 after reading Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland while recovering from a serious accident. “After experiencing the magic of this book, I wanted to be the magician who made the magic,” he said.

At 21, he married his childhood sweetheart, Wendy Holloway, who would later become a literary editor in London after the marriage disintegrated. Moorhouse went into journalism and became involved in activism and trade unions.

His first short stories were published in the late 60s. Many followed the same group of people in what he called a “discontinuous narrative … so it wouldn’t be seen as a failed novel. I pretended this was a literary form I’d been tinkering with.”

Along with Clive James, Germaine Greer, and Robert Hughes, Moorhouse became part of the “Sydney Push” – an anti-censorship movement that protested against rightwing politics and championed freedom of speech and sexual liberation. In 1975 he played a fundamental role in the evolution of copyright law in Australia in the case of University of New South Wales v Moorhouse, which found that the unsupervised use of photocopying machines infringed authors’ copyright.

Moorhouse wrote prolifically and with irreverence and humor about his passions – food, drink, travel, sex, and gender. Early in his fiction and later in his 2005 memoir, Martini, he wrote frankly about his bisexuality and androgyny. In his writing, he said he wanted to explore “the idea of intimacy without family – now that procreation is not the only thing that gives sex meaning”.

In 1985 he was appointed a Member of the Order of Australia for service to Australian literature. He received several fellowships including at King’s College, Cambridge, a Fulbright company, and the Woodrow Wilson Center in Washington. His novel Forty-Seventeen won the Australian Literature Society’s gold medal in 1988.

Prof Catharine Lumby, the author of an upcoming biography about Moorhouse, had put the finishing touches on the book at the weekend when she heard the news of his death.

Sign up to receive an email with the top stories from Guardian Australia every morning.

“When someone of his caliber dies, it feels like he belongs to the public,” she said. “I was a great fan ever since I was a teenager, but we met in the 90s and began discussing the biography in the early 2000s.”

She said he was “very in touch with his feminine side and supportive of young female writers. He understood women and wrote female characters so well.”

“But he wasn’t just a writer – he was an activist fighting censorship battles; very active in women’s liberation and gay rights and central to copyright reform in Australia. And he had a fascination with living well – he loved martinis and all the rituals around them, how you make the perfect one, who you drink it with, that spoke to a wider love of life.

“He had a very dry sense of humor and was a wonderful conversationalist – always in a restaurant, I don’t think he never cooked himself. It was a privilege to have known him.”